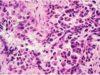

Researchers out of the UCLA Comprehensive Cancer Center are now using miniature lab-grown tumors to test a plethora of cancer treatments and find the most effective one. The tumors, called “tumor organoids,” are developed using a cancer patient’s own malignant cells, which allows their treatment to be designed specifically to fight their disease.

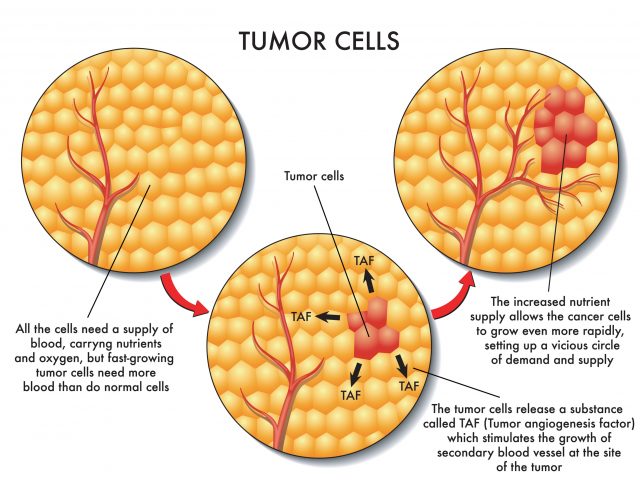

Recent advancements in medicine have allowed scientists to see the precise DNA makeup of a tumor, which gives them the chance to choose a drug that will accurately treat the disease. But because there are so many drugs to choose from, and not enough research on which tumor mutations respond to which therapies, it can be hard to come up with the exact drug or drug combination that will work.

Recent advancements in medicine have allowed scientists to see the precise DNA makeup of a tumor, which gives them the chance to choose a drug that will accurately treat the disease. But because there are so many drugs to choose from, and not enough research on which tumor mutations respond to which therapies, it can be hard to come up with the exact drug or drug combination that will work.

UCLA’s new study, published last week in Communications Biology, offers a way to combat this issue. Alice Soragni, Ph.D. and her team crafted “mini-tumors” in their laboratory from malignant cells taken from patients during surgery.

Two days after putting broken up pieces of the tumor onto petri dishes, the team had 3-d mini-tumors to use in testing different drugs and drug combinations. Because the tumors are small and thin, many of the drugs can easily reach the cells so that the team could see which treatments created the best reactions.

So far, this team has used ovarian and peritoneal cancer cells. Other studies have used cells from bladder, bowel, and gastrointestinal cancers. Although using these mini tumors has offered researchers the ability to test a variety of drugs, they won’t be successful for every kind of treatment. According to Soragni, “Right now, we can only test drugs which directly target the tumor. For example, we cannot test immunotherapies or types of drugs that require some other components besides the tumor itself.”

So far, this team has used ovarian and peritoneal cancer cells. Other studies have used cells from bladder, bowel, and gastrointestinal cancers. Although using these mini tumors has offered researchers the ability to test a variety of drugs, they won’t be successful for every kind of treatment. According to Soragni, “Right now, we can only test drugs which directly target the tumor. For example, we cannot test immunotherapies or types of drugs that require some other components besides the tumor itself.”

One of the greatest things about this process is that its relatively straightforward. A lot of it can be automated, which not only increases the speed, but also reduces the chance of human error. Once the tumor is processed and placed in the dishes, the team doesn’t have to deal with the cells anymore.

The entire process, which includes collecting the cells, formulating the tumors, and testing several drugs, takes about two weeks. Soragni said that results from the test “could potentially be available to the oncologist by the time the patient is recovered from surgery and ready to move forward with drug therapy.”

This new method offers great promise for patients recently diagnosed with cancer. Dr. Bone Rose, oncologist at Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University of Medicine, said that “being able to provide drug testing results on cancer samples within one week of surgery offers tremendous possibilites.”

More research still needs to be done before clinicians can say for sure how this will benefit cancer patients. A prior study did show that miniature tumors offered an effective and accurate way to see how patients would respond to certain treatments. Before this kind of procedure can reach medical clinics, Soragni and her team will have to address some intricacies and questions, but overall, the results are promising.