Biopsies are currently the best way to detect cancer, but they’re invasive, uncomfortable, and can take a while to come back. Researchers have long been trying to find ways to eliminate the need for biopsies, and a team from the University of Michigan may have found one. Their new device, which is currently being tested, may be able to detect cancer cells that are circulating in a patient’s blood.

Biopsies are currently the best way to detect cancer, but they’re invasive, uncomfortable, and can take a while to come back. Researchers have long been trying to find ways to eliminate the need for biopsies, and a team from the University of Michigan may have found one. Their new device, which is currently being tested, may be able to detect cancer cells that are circulating in a patient’s blood.

The University of Michigan team calls their new device “the epitome of precision medicine.” Dr. Daniel Hayes, Professor of Breast Cancer Research at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer center, believes that getting cancer cells from a patient’s blood could help researchers to learn more about the makeup of the tumor. He and his team created a wearable device that looks through the blood to filter out cancerous cells. If the device is found to be successful, it may eventually replace liquid biopsies (blood or urine samples) that pick up cancer markers.

Malignant tumors release cells into a patient’s blood, meaning that researchers could detect the presence of cancer through a blood sample. The problem is that the cancerous cells enter the bloodstream and circulate so quickly that they may not appear in one single blood sample. This issue is what sparked Dr. Hayes and his team to develop a device that actually searches for the cancerous cells.

Malignant tumors release cells into a patient’s blood, meaning that researchers could detect the presence of cancer through a blood sample. The problem is that the cancerous cells enter the bloodstream and circulate so quickly that they may not appear in one single blood sample. This issue is what sparked Dr. Hayes and his team to develop a device that actually searches for the cancerous cells.

The team has studied the device in dogs and they reported their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

The researchers have explained that finding cancerous cells as soon as possible is crucial. This is because when the cancerous cells do survive, they can travel to different parts of the body and create a new, metastatic tumor.

The most difficult part of developing the device has been to fit all of the necessary components into a device that must be small enough for someone to wear.

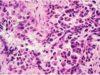

The chip that remains in the center of the device uses graphene oxide as a way of filtering the blood, and it’s able to detect over 80 percent of present cancerous cells. The dogs tested in the study were injected with human cancer cells (this procedure has no long-term effect on the animals as their immune system just sheds the foreign cells). The dogs were then given mild sedatives to allow the team to install the screening devices. The team also took blood samples from the animals every 20 minutes to screen for the cancer cells separately, using the same kind of design as the chip in the experimental devices.

The chip that remains in the center of the device uses graphene oxide as a way of filtering the blood, and it’s able to detect over 80 percent of present cancerous cells. The dogs tested in the study were injected with human cancer cells (this procedure has no long-term effect on the animals as their immune system just sheds the foreign cells). The dogs were then given mild sedatives to allow the team to install the screening devices. The team also took blood samples from the animals every 20 minutes to screen for the cancer cells separately, using the same kind of design as the chip in the experimental devices.

The team discovered that the device detected 3.5 times more cancer cells per millimeter of blood than the individual blood samples did.

So far, the device has shown great promise. The team hopes to improve its efficacy by increasing the speed of its blood-processing rate. There are still many more tests that need to be performed before the device can be considered safe and effective for human use, but Dr. Hayes hopes that people can enter clinical trials within 3 to 5 years.